“Something troubling you, Sebastian?” [John Scared] asked.

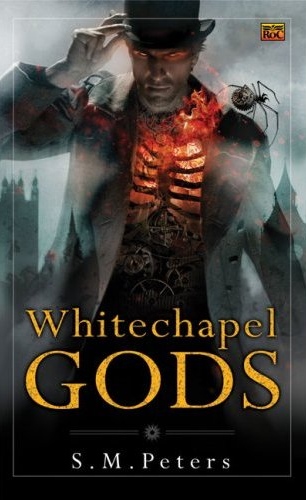

Sebastian Moran rubbed his round chin before answering. “Not that I would doubt your methods, sir, but your treatment of Mr. Boxer is…unsporting.” (Whitechapel Gods, S.M. Peters, 2008)

Despite what those closest to me seem to believe, or may try to tell you, I do actually read things besides Sherlock Holmes. Now, my reading habits tend to lean towards all things British, all things nineteenth century, and all things mystery (with a sharp turn towards detective fiction). I confess this fully, and without embarrassment. However, occasionally, I’ve picked up a book with the full intention of leaving the Great Detective to himself for awhile, and something Sherlockian manages to make an appearance in my reading material anyway.

In S.M. Peters’s Whitechapel Gods, for example, I was more than a little surprised to turn the page and find myself nose-to-nose with Colonel Sebastian Moran. So to speak. The novel is steampunk, and while that’s typically a nineteenth century genre, Peters’s novel is filled with so many wonderful, original characters that at times it’s a touch tricky to keep track of them all. And Colonel Moran? Well, after some brief interactions with the novel’s main villain (naturally), he disappears for large portions of the novel and is barely heard from again. Von Herder and his famous air gun also make slightly more substantive appearances.

In S.M. Peters’s Whitechapel Gods, for example, I was more than a little surprised to turn the page and find myself nose-to-nose with Colonel Sebastian Moran. So to speak. The novel is steampunk, and while that’s typically a nineteenth century genre, Peters’s novel is filled with so many wonderful, original characters that at times it’s a touch tricky to keep track of them all. And Colonel Moran? Well, after some brief interactions with the novel’s main villain (naturally), he disappears for large portions of the novel and is barely heard from again. Von Herder and his famous air gun also make slightly more substantive appearances.Which might leave the (Sherlockian) reader wondering: Why? Why is he here? Why bring him on board at all? Why not create someone new?

Similarly, in Libba Bray’s excellent Victorian young adult trilogy about nineteenth century heroine Gemma Doyle, I felt as if I were being given a sly wink-and-nudge at times throughout the series. In the second novel, Rebel Angels, one of the characters announces that she has taken rooms on Baker Street, which made me raise an eyebrow and smile, but not dwell too much on it. But, later on in The Sweet Far Thing, when Gemma has to set her bookshelf to rights, she very carefully and pointedly sets a copy of A Study in Scarlet on it. And I began to wonder.

I began to wonder if there wasn’t some sort of point to all of these references (which I won’t bore you with enumerating in their entirety, and I’m certain you have some of your own). I began to wonder if there wasn’t something to be said for them. It is entirely likely that at least some of these references are each author’s own personal regard for Sherlock Holmes, and that can answer away many of the more flippant references to street names and books on shelves. But Colonel Moran, true to form, proved to be a trickier devil for me to shake off.

And I began wonder… what if we look at it as a type of reminder, and not just some glorified bon mot on the part of the author? What if we were to think of it as the alarm that occasionally goes off on our internal clocks? That’s a large part of what detective fiction is all about, yes? It reminds us to look around. To see and observe. To notice the stain on the wall, the footprints in the grass, and the fingerprints on the chandelier, if necessary. To remember that no one is innocent and no one is guilty; not until we have the evidence to back it all up.

After all, in Talking About Detective Fiction (2009), P.D. James reminds us:

“…the detective story produces a reassuring relief from the tensions and responsibilities of daily life; it is particularly popular in times of unrest, anxiety and uncertainty, when society can be faced with problems which no money, political theories or good intentions seem able to solve or alleviate. And here in the detective story we have a problem at the heart of the novel, and one which is solved, not by luck or divine intervention, but by human ingenuity, human intelligence and human courage. It confirms our hope that, despite some evidence to the contrary, we live in a beneficent and moral universe in which problems can be solved by rational means and peace and order restored from communal or personal disruption and chaos.”

What I’ve come to realize is that when I stumble across a Sherlockian reference in the least likely of stories, the references mean more than a casual wink and nod at a knowing reader, it’s a reminder that, no matter how deep into the mires of insanity the story may have fallen, we will manage to dig out. There will be a solution, and a satisfying one, and it will make sense. Even if you have to tilt your head and squint for it to do so. Rights will be righted, and wrongs will be punished; and even if something or someone manages to escape, it shall all fit together in the end. And we will do it together, if only because we can.

So the next time I’m reading a book and the Diogenes Club or the Giant Rat of Sumatra or a Persian slipper filled with tobacco makes an unexpected appearance, I’ll probably still smile, raise an eyebrow, or even laugh (to the unending confusion of those dearest to me), but more importantly, I’ll be relieved. Because I’ll know that we’re going somewhere—this book, the author, and I—that it will have a point, and it will make sense. And I’ll be more likely to stick through to the end. Because that’s what Holmes would do.

It may seem a rather oblique method of conveyance, but I prefer to think of it as a careful one. As the man himself once said, "They say that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains…It's a very bad definition, but it does apply to detective work (STUD).”

COMING SOON: Book Review--The Sherlockian, by Graham Moore.

I wish you could see my delighted face and hear my exclamations of joy that you are, at last, writing a blog. This first post confirms my wildest hopes. Your ideas are fresh and provocative and I recognize the gently wry good humor I have come to look forward to, in micro bits, on Twitter. Not to mention your prodigious reading!

ReplyDeleteI think the theme you deduce from the threads of Sherlockian reference woven into so many works of late is very true and foundational to the lasting appeal of the character. Holmes is our rational oasis and he bestows a comfort that is much deeper than his cool exterior promises. We may sometimes identify with Holmes or Watson, but in the end isn't the reader (and most writers begin as zealous readers) most akin to the client who comes to Holmes to set things in order? I think it is fascinating that you begin your blog with this WHY question, about the proliferation of Holmes references, and I can't wait to read more such questions and answers, on whatever you are reading and musing about.