Darlene A. Cypser; Publisher: Foolscap & Quill (December 23, 2010)

During the course of the canon stories, Sherlock Holmes comes into contact with “four Violets,” either as clients or in some other capacity in his role at the world’s first consulting detective: Violet Hunter (COPP), Violet de Merville (ILLU), Violet Smith (SOLI), and Violet Westbury (BRUC). In addition to it being a relatively popular first name for Victorian girls, William Baring-Gould posited that Sherlock Holmes’s mother was named Violet, and other scholars have suggested the existence of a Holmes sister, also possibly named Violet. It’s fun to theorize how (or “if”) the name could have had some personal significance to Sherlock Holmes, and Darlene Cypser’s novel The Crack in the Lens offers a compelling new theory, and a fresh perspective on the Great Detective’s early years, with careful consideration to what readers already know.

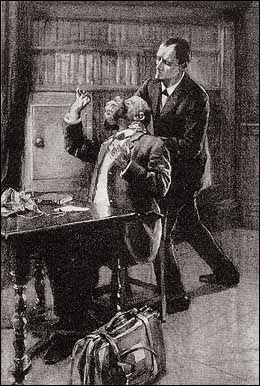

In 1871, Sherlock Holmes is seventeen-years-old, and just returned to Holmes Hall—his family’s Yorkshire estate—after two years on the Continent. Life at his family home is changing rapidly. Sherrinford, the oldest Holmes brother, is preparing to marry, and eventually assume his duties as the head of the estate. Mycroft is in London, working in his capacity for the British government. A new tutor has been hired to prepare Sherlock for university. And Sherlock meets Violet Rushdale, the daughter of a tenant farmer, on the moor that spring. Cypser’s young Sherlock cuts a striking, romantic figure—vibrant and in the prime of life—riding across his family’s estate. But there is a keenly felt distance between that young man, and the person who Dr. Watson will meet in 1881, in the laboratories of St. Bart’s.

The thorny issue with writing new back-story for Sherlock Holmes is that, while the canon leaves lots of room for speculation on the Detective’s early years, unless the author intends to rewrite or readapt the known back-story, there are certain plotlines that a reader already knows will not end well. A romance for a young Sherlock, no matter how passionate or compelling, is probably one of those plotlines. Before even opening the book, the reader already knows that Sherlock Holmes does not arrive at Baker Street with a wife on his elbow, so heartbreak clearly looms on the horizon from the outset for Sherlock and Violet. And that type of knowledge can sometimes be very distracting while reading—a reader can get anxious when constantly waiting for the axe to fall.

But the real strength of the novel lies outside of Sherlock’s youthful romance. The relationships that connect the Holmes family are rich, complex, and so very telling when considering the evolution of Sherlock’s character. Within the first few pages, the reader is introduced to Squire Holmes and his wife, and Sherlock neatly sums up their relationship:

“They were not close. He and his brothers had been brought up, as was not unusual for a family of their standing, by a succession of governesses and tutors. He had vivid memories of these, both good and bad, but his mother had always been a distant, fuzzy figure absorbed in the details of the running of the house and the maintenance of the squire’s social circle” (4).

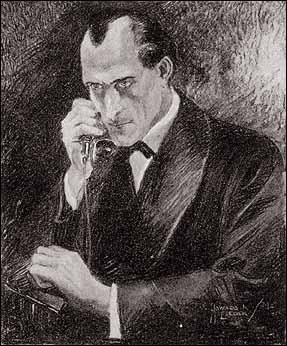

The narrative immediately brings to mind Jeremy Brett’s description of the Detective’s early life (or how the actor envisioned it): “I mean, I know what his nanny looked like, for example; she was covered in starch. She probably scrubbed him, but never kissed him. I don't think he probably saw his mother until he was about eight. Maybe caught a touch of the fragrance of her scent and the rustle of her dress.” Mrs. Holmes is an infrequent presence in the novel (perhaps fittingly so), but Squire Holmes is a formidable figure. He is an uncompromising mountain of a man, commanding unquestioning strength and obedience from everyone around him. It’s easy to see how his youngest son became a man who could bend fireplace pokers (SPEC), leap onto the backs of criminals to curtail them (SIXN), and narrowly avoid being struck down by a poisonous dart without blinking (SIGN).

Even more compelling is the relationship between the three Holmes brothers. Sherrinford, the eldest and nine years Sherlock’s senior, is not blindingly or incisively intelligent in the manner of his two younger siblings, but he is earnest and compassionate in a way that foreshadows the presence of Dr. Watson. When Sherrinford tells Sherlock, “You will always be welcome [at Holmes Hall] when I am squire” (118), the reader knows he is sincere. Mycroft, the middle child, appears on the page far less frequently, but always arrives at crucial moments, when Sherlock needs someone to speak to him in their native and shared language of logic and reason. And when the three brothers are together, there is a sense that the whole world could change—or even just their world—simply because they are all occupying the same space. Cypser effectively conveys the feeling that whatever the three brothers say to each other, whatever they decide when they are together, will have lasting, far-reaching consequences.

The author is also adept at setting a scene. The novel’s locales are as vivid and alive as any of the people. Holmes Hall is constantly bustling with activity, reminiscent of the beehives that Sherlock Holmes will turn to in his twilight years. The local village is colorful, filled with a diverse supporting cast of characters. The moors on which Sherlock and Violet conduct their romance are haunting, and beautiful. And when Sherlock visits York, with Sherrinford and his pretty new bride, there is a glimpse of the confident man who will one day walk the streets of London, directing his troop of Irregulars, knowing each alley and doorway. The echoes of who Sherlock Holmes will become walk behind him throughout the novel, just out of reach, but ever-present.

This novel will probably not be to everyone’s taste. The image of Sherlock Holmes, young and (sometimes quite literally) foolishly in love, might not sit well with some. In addition, The Crack in the Lens is not a typical Sherlock Holmes mystery, in the terms that readers have come to expect. The author herself said, in a March 12, 2011 interview on “The Baker Street Blog”: “You need to understand that my book is not a Sherlock Holmes mystery

But to borrow a line from “The Sussex Vampire,” there are “unexplored possibilities” here. Cypser’s teenage Sherlock is a man perched on the cusp of greatness, and her vision of how the Great Detective was ultimately fashioned is both devastating and captivating.

oOo

The Crack in the Lens is available in paperback and e-book formats from Amazon and Barnes & Noble. A full list of booksellers is available here. More information about the novel and its author is available on its website. Or follow the novel or Darlene Cypser on Twitter.

Show off your knowledge of Sherlock Holmes, his creator, and his world, to win a prize package of reference works! Entries are being accepted until 11:59p.m. EST on Saturday, May 21, 2011.