Outside of his 1939 production of “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” the Sherlock Holmes films starring Basil Rathbone were only tangentially linked to the stories of the canon, at best. In many instances, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original stories could be more accurately viewed as source material, rather than any real type of blueprint. They provided a framework, not any real form. But in 1944’s “The Pearl of Death,” when Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes advises Nigel Bruce’s Dr. Watson against hitting newspaper reporters in the teeth (an affectionate, though misguided, attempt at defending the Detective’s honor), there is more than an echo of Holmes’s original sentiment: “The Press, Watson, is a most valuable institution, if you only know how to use it."

|

| Image via www.sherlockholmesposters.com. |

That is not to say, however, that Conover—played by Miles Mander—is not a suitably diabolical figure. Indeed, the audience’s first glimpse of Conover is quite ominous; he looms menacingly in the back of a darkened car, cloaked in shadow, waiting for his associate Naomi Drake (played by Evelyn Ankers). In many ways, this scene echoes how the audience would first view Professor Moriarty in the 2009 Warner Bros. movie. In that film, as Moriarty sits with Irene Adler (played by Rachel McAdams), he is seen mostly in darkness, only a cuff and coat sleeve visible, and lurking in the back of a carriage. Both Adler and Drake appear to school their nerves in the presence of their intimidating companions, but there is an unmistakable undercurrent of terror that they cannot quite conceal, and which feeds the audience’s perception of the villains.

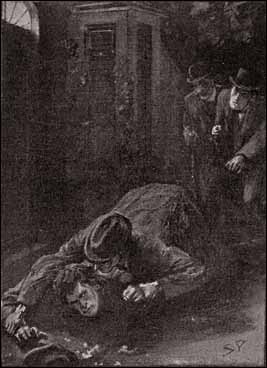

Another interesting addition to this film was the character known only as “The Creeper,” (played by Rondo Hatton). The Creeper is a silent, lurking, violent killer, whose distorted features only serves to heighten his chilling presence. Hatton suffered from acromegaly, a pituitary disorder, which caused his disfigurement. But this fearsome hooligan, who serves Conover and is responsible for almost all of the violence to person and property throughout the film, stands in the place of a character from the source material. As Dr. Watson describes the photograph of Beppo: “It was evidently taken by a snapshot from a small camera. It represented an alert, sharp-featured simian man, with thick eyebrows and a very peculiar projection of the lower part of the face, like the muzzle of a baboon.” And when Beppo is captured: “As we turned him over I saw a hideous, sallow face, with writhing, furious features, glaring up at us, and I knew that it was indeed the man of the photograph whom we had secured.” The Creeper is no more peaceful than Beppo in resolving his affairs in “The Pearl of Death,” and the character would later appear in two more films, unrelated to Sherlock Holmes.

“'The Pearl of Death' is noteworthy in that it really saw the transition of Rathbone and Bruce into the characters they were playing. Universal practically eliminated the names Holmes and Watson from their advertising from this film onwards. Typical blurbs now ran: ‘Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce Crack the Mystery of The Pearl of Death’ or ‘Rathbone & Bruce – The Masterminds Tackle The Master Crimes’. The names and identities of the actors had become so synonymous with those of the characters they were playing that as far as Universal was concerned—and the public too—using one name was as good as another” (57).

Of course, “The Pearl of Death” also features the ceramic busts of Napoleon, their methodical destruction, and the valuable pearl hidden inside one of them, in addition to new archenemies and their fearsome companions. The film also deviates in important ways. But the manner in which the film hearkens back to its source material is suggestive. When Watson asks Holmes if he is certain that the missing pearl is inside the final bust, Holmes dismissively says: “If it isn’t, I shall retire to Sussex and keep bees.” Such is typical of the type of tributes an avid Sherlock Holmes fan would find in “The Pearl of Death.” While some of Universal’s Sherlock Holmes films seem to hearken back to the original stories in terms of only one plot point, character, or narrative device, this film seems to recognize the spirit of the original SIXN, and seeks to embody it globally.

oOo

“Better Holmes & Gardens” now has its own Facebook page. Join by “Liking” the page here, and receive all the latest updates, news, and Sherlockian tidbits.

I'm not absolutely sure, but I think this film may have been my introduction to Sherlock Holmes. I would have been about ten watching it in San Antonio, where we had moved from Pennsylvania, following my dad from airbase to airbase. I recall being really frightened by a Sherlock Holmes movie and The Creeper could easily have been responsible.

ReplyDeleteBut what I most recall is the idea of the Great Detective making sense of the world and responding to that. This was during the period of a lot of airbase closures and we moved back and forth between Texas and Pennsylvania a lot and I felt like I was at the whim of my parents (although it was really the government). To me, Holmes (rather than Watson) was my “one fixed point in a changing world.”

Great post as always, Jaime.

I love these early Holmes' films. I haven't seen this one, although the story is a favorite.

ReplyDelete