“As I write these words, it occurs to me that the story is in fact a timely one, in that it demonstrates the evils which a science left to itself may inflict upon an unsuspecting mankind. A culture which allows zeppelins to rain death and destruction upon the cities of men and heavy guns to pound civilisation back into the dust whence it came is a culture which has yet to learn from its mistakes. It is therefore hoped that the chronicle which follows will serve as a lesson to the world that the laws of nature are inviolate, and that the penalty for any attempt to circumvent them is swift and merciless. Assuming, that is, that there will still be a world when the present cataclysm has run its course” (21-2).

When his friend, Sherlock Holmes, strayed beyond the boundaries of reason and logic, Dr. Watson was known to express a measure of incredulity. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, he says to Holmes, “And you, a trained man of science, believe it to be supernatural?” Watson is, of course, referring to Holmes’s view on the origin and true nature of the Baskerville hound, but it is only one of a few moments throughout the canon, in which Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson are confronted by a seemingly supernatural or otherwise inexplicable force, only to find that it ultimately has a rational explanation. It is also no new theme in Sherlock Holmes pastiche to bring the Great Detective face-to-face with the inexplicable. The conclusions of such stories can vary from a traditional, rational ending with Holmes’s deductions verified by evidence and fact – to a fantastic, paranormal conclusion that leaves Holmes shaken and unsure. Likewise, it is nothing new to pair Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson with famous contemporary literary and historical figures, either as allies or as adversaries.

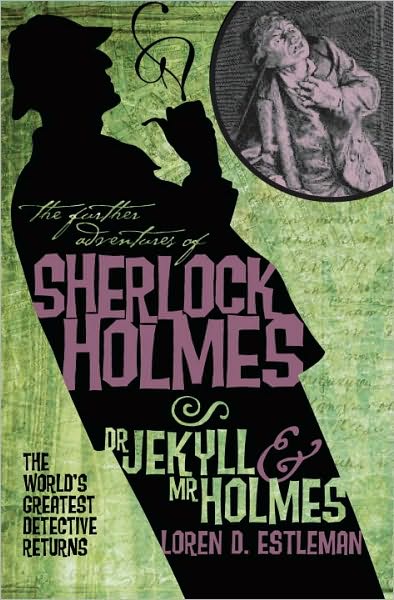

When his friend, Sherlock Holmes, strayed beyond the boundaries of reason and logic, Dr. Watson was known to express a measure of incredulity. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, he says to Holmes, “And you, a trained man of science, believe it to be supernatural?” Watson is, of course, referring to Holmes’s view on the origin and true nature of the Baskerville hound, but it is only one of a few moments throughout the canon, in which Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson are confronted by a seemingly supernatural or otherwise inexplicable force, only to find that it ultimately has a rational explanation. It is also no new theme in Sherlock Holmes pastiche to bring the Great Detective face-to-face with the inexplicable. The conclusions of such stories can vary from a traditional, rational ending with Holmes’s deductions verified by evidence and fact – to a fantastic, paranormal conclusion that leaves Holmes shaken and unsure. Likewise, it is nothing new to pair Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson with famous contemporary literary and historical figures, either as allies or as adversaries. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Holmes, by Loren D. Estleman is the second of the author’s two Sherlock Holmes pastiches (Sherlock Holmes vs. Dracula: The Adventure of the Sanguinary Count was originally published in 1978), and is, by the author’s own admission, the more cerebral of the two novels. “Bereft of physical evidence – telltale footprints, broken pen-points – Holmes is forced to track the vanished Jekyll’s movements through the books he studied in his quest for the cause and cure of personal evil… The greatest advantage enjoyed by the writer of fiction intended to be read is also the biggest roadblock to adaptation to the screen” (218). And as in the plot of his first pastiche, Estleman does not deviate from the original source material – in this case, the Robert Louis Stevenson novella, the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Instead, he has Sherlock Holmes work his own path, using his own devices – occasionally colliding with the plot of Stevenson’s story – but never altering it. The result is a novel that is equal parts traditional Sherlockian mystery, paranormal variation, and literary and historical convergence.

The crux of Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is that the story manages to present both a logical (if not rational) explanation for what happened to Henry Jekyll and Edward Hyde, while at the same time emitting an unnatural quality. At the heart of the mystery that is Dr. Henry Jekyll are science and a chemical formula that involves no demons, no unholy blood rituals, or shortsighted partnerships with the occult. It is science and rational thought that drive the separation of the friendly and sociable Jekyll from his darker, more destructive impulses as represented by Edward Hyde. It is a science that doesn’t hold up under any sort of scrutiny (like many ideas born of fiction), of course, and there is something so deviant about the whole process that it gives off the impression of something supernatural. And the Great Detective’s reaction to seeing the mystery in full reveal, only serves to augment that impression. According to Dr. Watson:

“Out of the corner of my eye I glimpsed a pale and shaken Sherlock Holmes, and thus received a mirror-view of myself in that moment. Though it was obvious that he had known what was coming, the naked fact of its happening in his presence was quite another thing. His jaw fell open slightly and his eyes were started from their sockets, reactions which in him were the equivalent of a normal man’s fit of hysterics” (196).

Loren Estleman’s pastiche loses none of the conflicting atmosphere of Stevenson’s original – he features a Great Detective viciously torn between what his deductions have told him must be so, and what his rational mind tells him patently cannot be. After he recovers from the shock of seeing Hyde transform into Jekyll, and the outrageous events that follow, one of Holmes last acts in the drama is to throw Dr. Jekyll’s notes and chemical diagrams onto the fire – ensuring that the truth of what occurred is lost to the world. “And with Jekyll’s notes go the chances of anyone ever repeating his diabolical experiments,” says Holmes (207). Again, the Detective’s logical deductions insist that what has occurred is scientific and could therefore be repeated. But the unnatural horror of what has happened during the evening drives him to ensure that it can never be again.

According to Loren Estleman, he considered Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Holmes to be the better book, in contrast to his earlier Sherlock Holmes vs. Dracula. “It’s a more mature work,” he says, “the Sherlockian rhythms are more faithful to the model, and the title is superior. Sherlock Holmes vs. Dracula still sounds too much like a film directed by Edward Wood, Jr. I only settled on it because I couldn’t think of a better way to get the names of both hot-button characters up front” (221). Estleman’s pastiche also features a Sherlock Holmes in a disguise that completely deceives Dr. Watson (yet again), a Dr. Watson who is largely left out of his friend’s machinations and yet still worries endlessly for his well-being, and many other more traditional and expected Sherlockian elements, rather than just a moderately unhinged doctor who has managed to physically separate the aspects of his personality. But like any good pastiche, Estleman’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Holmes harkens back to the canon, and in particular “The Adventure of the Speckled Band,” in which Sherlock Holmes reminds his reader: “Subtle enough and horrible enough. When a doctor does go wrong he is the first of criminals. He has nerve and he has knowledge."

According to Loren Estleman, he considered Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Holmes to be the better book, in contrast to his earlier Sherlock Holmes vs. Dracula. “It’s a more mature work,” he says, “the Sherlockian rhythms are more faithful to the model, and the title is superior. Sherlock Holmes vs. Dracula still sounds too much like a film directed by Edward Wood, Jr. I only settled on it because I couldn’t think of a better way to get the names of both hot-button characters up front” (221). Estleman’s pastiche also features a Sherlock Holmes in a disguise that completely deceives Dr. Watson (yet again), a Dr. Watson who is largely left out of his friend’s machinations and yet still worries endlessly for his well-being, and many other more traditional and expected Sherlockian elements, rather than just a moderately unhinged doctor who has managed to physically separate the aspects of his personality. But like any good pastiche, Estleman’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Holmes harkens back to the canon, and in particular “The Adventure of the Speckled Band,” in which Sherlock Holmes reminds his reader: “Subtle enough and horrible enough. When a doctor does go wrong he is the first of criminals. He has nerve and he has knowledge." oOo

“Better Holmes & Gardens” now has its own Facebook page. Join by “Liking” the page here, and receive all the latest updates, news, and Sherlockian tidbits.

I -love- this book. The Holmes/Watson dynamic is excellent. Great review!

ReplyDeleteArthur Conan Doyle believed in supernaturalism and spiritualism. He often held seances to communicate with those who had passed into the next world. That he created a character who relied on logic and science says a lot about his curious mind.

ReplyDelete