Here are questions which any pasticheur must ask before embarking upon a new Sherlock Holmes story: how closely do I cleave to the style and milieu established by Doyle? With what degree of fidelity do I try to emulate the originals? How closely can I approach Doyle’s intentions? And how far can one diverge from them before the result ceases to feel like Holmes at all? The range of answers has been considerable – from those who endeavour to come as near as possible to the kind of thing that Doyle might actually have written (Bert Coules’ artful Further Adventures or Adrian Conan Doyle and John Dickson Carr’s pallid Exploits) to those who take the title character and, as in those accounts in which the sleuth is discovered battling zombies or meeting Tarzan of the Apes, place him in a story which Doyle would never have countenanced. Then there are the spoofs and the send-ups, the fashionable reimaginings and that subgenre which subverts Doyle’s originals to suggest that the stories in the Strand were in some sense mendacious (Robert Lee Hall’s bizarre Exit Sherlock Holmes; Michael Dibdin’s blackly comic The Last Sherlock Holmes Story; Nicholas Meyer’s ingenious The Seven-Per-Cent Solution).

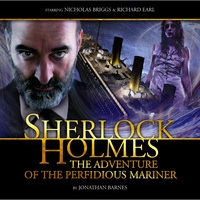

All of this has been much on my mind lately as I’ve just contributed a pastiche of my own – The Adventure of the Perfidious Mariner – to a line of high-quality, full-cast Sherlock Holmes audio dramas produced by the British company Big Finish (specialists also in Doctor Who, Dark Shadows, Stargate and more). Mine is their eighth Holmes tale and so far the producers, eager to cater for all tastes, have answered those questions about fidelity to Doyle in a variety of ways – from ultra-faithful adaptations (The Hound of the Baskervilles; The Final Problem) to straight pastiche (George Mann’s impressively authentic The Reification of Hans Gerber) to the wilder possibilities of the doctor and the detective squaring up to Count Dracula (in a version of David Stuart Davies’ novel, The Tangled Skein).

|

|

| Artwork Credit: Alex Mallinson |

I’m proud of the script for The Adventure of the Perfidious Mariner and I was more than delighted with the cast. Holmes and Watson are played by Nicholas Briggs and Richard Earl, both highly accomplished British stage actors (and, in Briggs’ case, well-known to television viewers as the voice of the Daleks in Doctor Who) and their interpretations of their famous roles are emblematic of Big Finish’s take on Holmes – a melding of the traditional and the revisionist. Briggs is a mostly classical Sherlock, warmer than Benedict Cumberbatch, less eccentric than Jeremy Brett while remaining spikier and more intolerant than Basil Rathbone. Earl, playing the capable military man of the stories, is as soberly efficient as Edward Hardwicke though with a little of Jude Law’s dash and just a scintilla of the lovability of Nigel Bruce. Perhaps the team they most resemble – in their brio and full-blooded theatricality – is the delightful 1950s pairing of John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson. Meanwhile, Michael Maloney – that distinguished Shakesperean and frequent collaborator with Kenneth Branagh – plays Ismay with all his customary intellect and skill.

As is often the case in Baker Street, one adventure suggests another. In the course of writing the script – and also while listening to the cast bring it to life in the recording studio – something struck me as odd which had never, in repeated readings of the canon, seemed so to me before. Why does Holmes retire? He can’t be particularly old and his powers show no signs of waning (indeed, in His Last Bow, Holmes seems to be at the very top of his game). And so I began to wonder whether something might have happened to trigger his resignation, something about which the doctor has hitherto remained tight-lipped.

There are no answers suggested or theories propounded in The Adventure of the Perfidious Mariner – but only hints and thinking aloud. Now, of course, it’s nagging at me – the question of why Watson is so coy about Holmes’ motives for devoting himself to the bees. I’m still thinking about it and I’ve set nothing down on paper but perhaps, in some form or another, I’ll return to Doyle’s creations again and explore them just a little further – always bearing in mind, of course, Sir Arthur’s invitation about marriage and murder and more. How generous he was to grant us all such freedom.

oOo

|

| Photo Credit: Amelia Wallace |

The Adventure of the Perfidious Mariner is available now and can be purchased directly from Big Finish (on CD: http://www.bigfinish.com/Sherlock-Holmes-The-Adventure-of-the-Perfidious-Mariner or as a download: http://www.bigfinish.com/Sherlock-Holmes-The-Adventure-of-the-Perfidious-Mariner-DOWNLOAD-ONLY

You can read more about Big Finish’s range of Sherlock Holmes adventures at: http://www.bigfinish.com/ranges/Sherlock-Holmes

No comments:

Post a Comment