"Watson won't allow that I know anything of art, but that is mere jealousy, because our views upon the subject differ. Now, these are a really very fine series of portraits." (HOUN)

I come by my uniquely passionate personality honestly – at least, that’s what I like to tell myself. When I was growing up, my mother was (and still is, actually) an ardent devotee of all things Arthurian. My childhood home was resplendent with reproductions of medieval tapestries and framed prints of dragons. The shelves of my mother’s not insignificant library overflowed with a wide and unique array of literature in her chosen field, including a rather beautifully illustrated children’s edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which she had to keep on her own shelves because the vivid sketches of the beheaded green knight (complete with bloody stump – trust me, I remember) made my sister and I scream in unholy terror. I myself am now the owner of two of her favorite Arthurian swords, which she had to give up when she moved into a smaller living space (her immense library was also one of the casualties of the move). And while she would never admit it outright, I imagine she must have felt a speck of disappointment that neither of children ever shared her interest.

But what she must have recognized in her children was elements of her own personality – and all of its obsessive, ardent nuances – and she was good at planting seeds. I remember vividly being a teenager – my discovery of Sherlock Holmes and his world still fresh and new – and being excited to learn that the 1959 version of The Hound of the Baskervilles (starring Peter Cushing) was going to be on television that afternoon. “No,” my mother said, taking the remote from my hand. “You can’t watch that one. It’s too scary. It gave me nightmares as a child.” Well, saying something like that to a teenager is essentially like waving red at a bull, and my mother must have known it. She only put up the most cursory of arguments when I protested. I didn’t find the movie even remotely frightening – heaven knows that I had seen infinitely more gruesome things by the time I was a teenager – but watching that film with my mother has always been a very sweet memory.

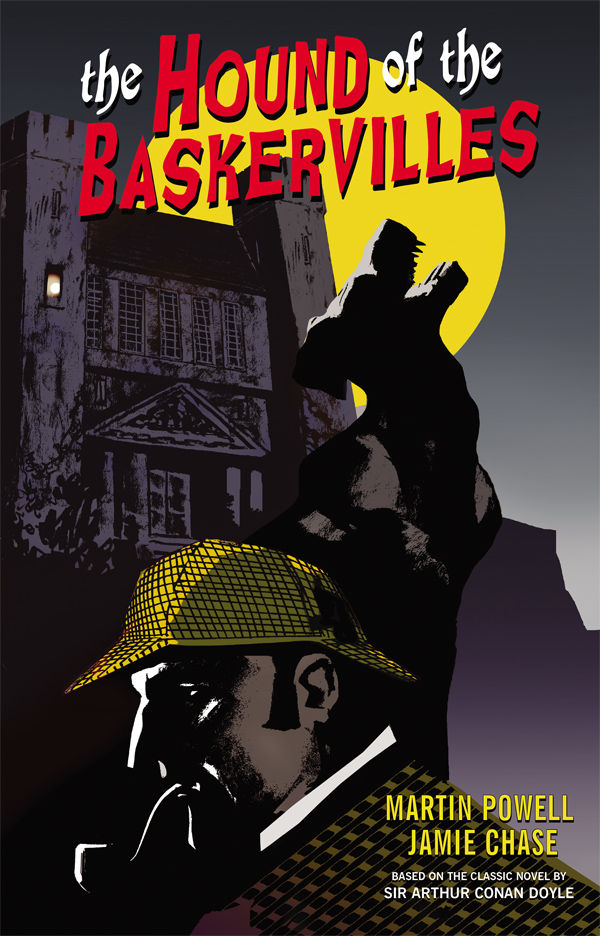

As such, it was a thrill to open Martin Powell’s and Jamie Chase’s new graphic novel adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles and be instantly reminded of that time. There’s

more than a little bit of Hammer Horror’s Hugo Baskerville about Chases’s

rendition. The iconic blood-red riding jacket and distinctive eighteenth

century hairstyle of the famous villain are immediate visual cues. Suddenly, I’m

watching David Oxley chase an unfortunate young woman across the moor, with the

moon highlighting his silhouette as he lays eyes on the Hound for the very

first time. And a few pages on, with the slope of his brow and the curve of his

hawk-like nose, it is Peter Cushing ensconced in the Baker Street sitting room,

draped in the famous purple dressing gown and wielding his eyebrow like a

weapon. However, it’s not just the Hammer Horror version of HOUN that leaps

from the pages of this novel. There is also a Dr. Mortimer whose thin mustache

and distinctive, round spectacles are more reminiscent of the Mortimer seen in

the 1939 film version of HOUN starring Basil Rathbone, Nigel Bruce and Lionel Atwill (as the late Sir Charles’s closet friend). In the strikingly

handsome features of Chase’s Sir Henry, there is more than a little of Richard Greene’s face and all his classic, movie star qualities. And in the single

panel in which Sherlock Holmes answers Dr. Watson’s question about the

existence of the Hound, (saying simply, “It does.”) it is difficult for the

reader not to hear Jeremy Brett’s delivery of that iconic line, complete with

his sonorous timbre.

As such, it was a thrill to open Martin Powell’s and Jamie Chase’s new graphic novel adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles and be instantly reminded of that time. There’s

more than a little bit of Hammer Horror’s Hugo Baskerville about Chases’s

rendition. The iconic blood-red riding jacket and distinctive eighteenth

century hairstyle of the famous villain are immediate visual cues. Suddenly, I’m

watching David Oxley chase an unfortunate young woman across the moor, with the

moon highlighting his silhouette as he lays eyes on the Hound for the very

first time. And a few pages on, with the slope of his brow and the curve of his

hawk-like nose, it is Peter Cushing ensconced in the Baker Street sitting room,

draped in the famous purple dressing gown and wielding his eyebrow like a

weapon. However, it’s not just the Hammer Horror version of HOUN that leaps

from the pages of this novel. There is also a Dr. Mortimer whose thin mustache

and distinctive, round spectacles are more reminiscent of the Mortimer seen in

the 1939 film version of HOUN starring Basil Rathbone, Nigel Bruce and Lionel Atwill (as the late Sir Charles’s closet friend). In the strikingly

handsome features of Chase’s Sir Henry, there is more than a little of Richard Greene’s face and all his classic, movie star qualities. And in the single

panel in which Sherlock Holmes answers Dr. Watson’s question about the

existence of the Hound, (saying simply, “It does.”) it is difficult for the

reader not to hear Jeremy Brett’s delivery of that iconic line, complete with

his sonorous timbre.Chase’s illustrations are atmospheric and impressive, but not just for the way in which they harken back to some of the most famous cinematic adaptations of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s most famous novel. The color palette is striking and mesmerizing. Dominated by a dark, sometimes harsh, selection of hues, the occasional pinpoints of color have just that much more impact: the rosy blush of sunlight coming through a window, the golden glow of a single candle, or – as mentioned previously – the ominously, maliciously red jacket on Sir Hugo. In his illustrations, Chase uses color with a stunningly magnificent expertise, and to the fullest, most profound impact.

For his part, Martin Powell has managed to craft a gorgeous adaptation of Doyle’s original novel. As an adaptation, not a duplication, there are elements of the story that are missing. For instance, readers who tend to skip over Dr. Watson’s lengthy, sometimes tedious, descriptions of landscape and setting will be pleased; there is none of that present – the drawings certainly give voice to those elements on their own. As another reviewer has pointed out, the famous phrenological exchange between Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Mortimer is also missing. The story is streamlined, with much of the exposition and introspection omitted. What remains, however, practically vibrates with intensity. Many of Watson’s reports to Holmes (whom he believes is back at Baker Street) are written across the background of a panel, while the action plays out in the foreground. It’s a powerful and evocative way of showing the complexity of Watson’s role, and the depth and intricacy of the story that Doyle wove together.

Powell wields his chosen dialogue for maximum emotional effect. When Watson speaks to a shadowy figure off-panel, saying simply: “You! I thought you were still in London!” There is a frisson of fear, even if readers already know that they will turn the page to find the Great Detective as the man being addressed. When Holmes tells his friend: “Your reports did it justice, Watson. The house does, indeed, have a menacing personality all its own” – that personality is practically tangible, as the reader sees Sherlock Holmes as a small, isolated figure standing in the grand hall of the Baskerville estate. Martin Powell’s story and Jamie Chase’s artwork are symbiotic, and they likewise do more than justice to a story that is more than a classic – Doyle’s HOUN is as immortal as the Hound itself.

Occasionally I’m asked by someone new to the Canon about where they should start – what short story or novel is a great introduction the Great Detective? Invariably, they wonder if it shouldn’t be The Hound of the Baskervilles – it is the most recognizable, after all, and the one that most people seem to have on their bookshelves, even if they have never read it. I usually shy away from that suggestion – explaining that Sherlock Holmes is actually absent for the majority of the story and that the lengthy and frequent descriptive passages are often tiresome. Powell and Chase’s adaptation of HOUN alleviates both of those issues. With Powell moving Dr. Watson’s activities and the related action into the foreground, Holmes’s absence really seems secondary. And Chase’s artful illustrations mitigate the need for prolonged descriptions and soliloquies on landscape. The resulting work is the version of HOUN that readers visualize when they pick-up the original novel, that they take away with them with they watch one of the many film or television adaptations. It is, in many ways, the best possible version of HOUN and does justice to the story's enduring nature.

oOo

The Hound of the Baskervilles, adapted by Martin Powell and Jamie Chase, can be found on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Martin Powell can be found online at: http://martinpowell221bcom.blogspot.com/.

“Better Holmes & Gardens” has its own Facebook

page. Join by “Liking” the page here,

and receive all the latest updates, news, and Sherlockian tidbits.

Thank you for such a well written review.

ReplyDeleteMichael Hudson/Sequential Pulp Comics