|

| Ick. |

Having discovered that the mysterious man on the Tor—whom he had glimpsed briefly one dark evening with Sir Henry Baskerville—is none other than his good friend Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson follows the Detective into the rough stone hut that has served as Holmes’s dwelling for the past few days. Holmes serves Watson some of his “meager refreshment”—a repulsive, lumpy, brown soup—that Holmes pours proudly and sloppily onto a plate, before encouraging Watson to eat. The Doctor looks revolted, and tries to distract Holmes with a few moments of conversation about the case before them. Eventually Holmes tries again: “Watson, please, do try my stew.”

Cornered, Watson sighs: “It’s quite disgusting, Holmes.”

“Yes,” Holmes sighs in return. “Yes, it is. Well, it’s better when it’s hot.”

That statement can be used to neatly sum-up Granada Television’s version of The Hound of the Baskervilles. In other words, it’s not so much about what is inside the package, as it is about the presentation. With HOUN, it’s not about the story itself—there are few people who do not know at least something about the horrible hound, the menacing moors, and the terrible family curse. As The Stage said, “Like a child who likes to read the same Pooh story time and time again, it’s not so much the narrative that you love as the manner of its telling” (Davies 145). With the 1988 adaptation of HOUN, what is central is the issue of conveyance, not concept.

Granada’s HOUN actually has quite a bit to recommend itself, beginning with the fact that this version of HOUN actually features a young man (Alastair Duncan) in the role of Dr. James Mortimer, as opposed to the elderly medical man as which he is so often portrayed. Duncan is certainly more in keeping with the Detective’s famous description of the doctor: “…a young fellow under thirty, amiable, unambitious, absent-minded, and the possessor of a favourite dog, which I should describe roughly as being larger than a terrier and smaller than a mastiff.” Although Duncan’s Mortimer cannot be described as completely “unambitious,” as perhaps he is “selectively ambitious.” Dr. Mortimer seems more than willing—even pleased—to accompany Holmes and Watson as they capture Jack Stapleton at the film’s climax. He even hunts the rabbits that have been destroying his excavation site with lively—if somewhat gruesome—energy.

Kristoffer Tabori fills the role of Sir Henry Baskerville—a character that the late Richard Valley described as somewhat thankless: “Sir Henry’s primary plot functions are to fall in love with the wrong woman and act as bait for a hungry dog…” It certainly cannot be argued that the baronet does—and more importantly, must do—both of these things; but he is, as I have discussed at-length elsewhere, more than just fodder for the hound. Tabori’s performance is subtle, almost to the point of being dramatically understated, and nowhere is that more evident than in Sir Henry’s interactions with Beryl Stapleton (Fiona Gillies). Tabori’s Sir Henry is neither infatuated nor foolishly love-struck; he does not fawn over “Miss” Stapleton. Instead, he rather seems quietly in awe of her, as if moved to softness and gentility when in her presence. As Valley describes Sir Henry and Beryl’s final moment on-screen together: “…[Tabori] contributes a fine, ambiguous moment when, surviving the hound’s dinner arrangements, he comes face to face with the one who has simultaneously betrayed and tried to save him.”

|

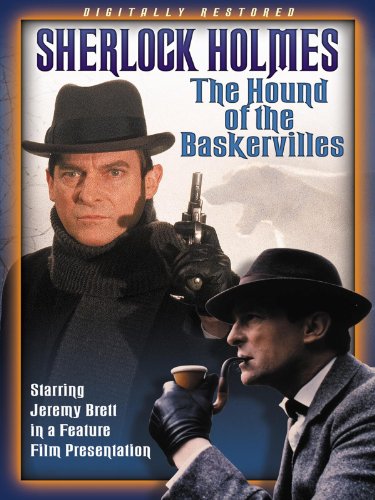

| Kristoffer Tabori as Sir Henry Baskerville (left), and Jeremy Brett as Sherlock Holmes (right) |

But Granada’s adaptation is not just about the supporting characters, of course. I don’t typically recommend The Hound of the Baskervilles to friends who have never read a Sherlock Holmes story before; this is mostly because they are always surprised to find how little Sherlock Holmes is actually in this story, for all that it is probably his most famous adventure. Granada’s version reflects this element of the original text in that Jeremy Brett is only on-screen for a total of about thirty minutes throughout the entire film. (In fact, some of his scenes are not even new footage, but instead are shots that some viewers may recognize as having been lifted directly from Granada’s version of “The Greek Interpreter.”) HOUN is really Dr. Watson’s tale.

Edward Hardwicke plays a Watson that the viewer can easily commit to following around Dartmoor, but more importantly, a Watson that we want to follow as he investigates. According to Valley:

“Hardwicke embodies the two most important qualities of Watson in ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’: he’s a man with whom we’re willing to linger while the more dynamic Holmes is not on and; second, he’s of sufficient grit and intelligence not to make us think Holmes has lost his mind by sending Watson to Dartmoor in his stead.”

Hardwicke’s Watson seems a bit flabbergasted, but not truly put-out, when Holmes volunteers the Doctor’s services to Sir Henry at Baskerville Hall. It’s as if he knows his friend well enough that he was expecting something like this. And when the two men are reunited outside out the stone hut, and Watson learns that Holmes has been following him all the while, the Doctor’s reprimand is gently chiding, not irate: “I deserve better at your hands, Holmes. You use me and do not trust me.” It’s easy to imagine Sherlock Holmes as genuinely remorseful in the face of such a gentle reproof. Their interactions do not degenerate into childish, angry bickering. And Hardwicke’s Watson certainly does not bumble around foolishly and make silly proclamations to old beggars who are clearly the Detective in disguise (“I am Sherlock Holmes!”). Holmes and Watson’s relationship is not at question in this version of HOUN; their friendship is solid and stable. Hardwicke’s Watson trusts Brett’s Holmes implicitly, and Brett’s Holmes is justifiably reliant on Hardwicke’s Watson.

|

| Basil Rathbone (left) and Nigel Bruce (right) in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939): Oh, do shut your mouth, Watson. You're letting in the flies. |

According to The Ritual, a theatrical magazine, “The definitive version of The Hound is sort of a Sherlockian Holy Grail. Granada’s production is one of the best—but it is far from definitive.” There’s quite a bit in this adaptation that the viewer does not typically see in other versions of HOUN: a young Dr. Mortimer, a Sir Henry with substance, a compelling Watson, and a superstitious Holmes. But as the star himself admitted, the film is often laborious and slow, and much of the dramatic tension seems to escape with every overly-long shot of landscape. The Ritual is probably correct in that Granada’s adaptation is not the “Holy Grail” of The Hound of the Baskervilles films. But it has many of the essential elements, which other versions usually lack, and perhaps it can still be used as a beacon, to prevent other versions of HOUN from being lost on the moors.

oOo

Only one day left to enter the blog contest! Share your ideal Sherlock Holmes story, and win a prize package of pastiches. The contest is open until 11:59p.m. EDT on July 23.

Sources:

• Stuart Davies, David. Starring Sherlock Holmes: A Century of the Master Detective on Screen (January 2006).

That scene with the stew is probably the best of this episode! Very well done on both actors’ parts. (Holmes is more excited here then when doing a big reveal - and when Watson shoots him down with the undeniable truth, Holmes sighs and has to admit it is disgusting. Then adds that line about it being better when hot - priceless!)

ReplyDeleteI don't agree that Holmes was superstitious in this version. In fact, to compare apples to apples, if we look at ‘The Last Vampyre’ (Granada), I think Holmes is uncharacteristically single-minded. Holmes is a man that won’t make a declaration until he puts the facts together and comes up with the truth. One of my favorite ‘lines’ or ‘themes’ is his belief that you don’t dismiss what doesn’t fit just because it doesn’t fit. If it doesn’t fit, you’re not looking at everything correctly. So to dismiss supernatural hounds or vampires – while he is a man of science – seems out of character. He may not believe it and will conduct his investigation on those principles but he’ll – in my opinion – be more like he was in Granada’s ‘Hound’ and not answer than Granada’s ‘Vampyre’ and make fun.

And as far as “the film is often laborious and slow, and much of the dramatic tension seems to escape with every overly-long shot of landscape” – that is totally on point with canon. How many times did I shout in my head while reading ‘Hound’ – “It’s a moor! I get it!!”

As always, wonderful, cool Post!!!!

Beautifully observant, as befits someone who is spending a large share of her consciousness in the company of Holmes. You provide an illuminating "close reading" of the Granada HOUN. It has always been one of the hardest stories for me to warm up to, and I agree it is not the best place to start in the Canon.

ReplyDeleteI think all concerned acquitted themselves well in the Granada teleplay. Whatever bagginess or ambiguity is inherent in the novel. I did a double-take at the mention of "Alastair Duncan" but realized I must keep my "Alastairs" and "Alistairs" apart (not to mention the inexplicable "Alasdairs"!). A wonderful conclusion: it is "a beacon, to prevent other versions of HOUN from being lost on the moors."

Perhaps one of the most difficult aspects of adaptation, of any novel, is getting the pacing right. I agree that the greatest failing of this version of HOUN is that it often loses its dramatic tension. A good adaptation adapts whatever qualities in the source material won't work on screen (big or small). I would have loved to see Brett have that second shot - with less lanscape shots and a tighter script with a touch more momentum.

ReplyDeleteOh great, now I have to take this off the dusty shelf and rewatch it, just like I did The Greek Interpreter after another of you postings. Oh agony!

ReplyDelete@Live Out Loud: Thank you for your thoughtful comment! Perhaps the right word isn't "superstitious." Maybe it's "shaken" or something similar. As you said, he can't count out the notion of a demonic hound, but as a man of science, it still doesn't sit well with him. Then you have Dr. Mortimer—another man of science who impressed Holmes—who seems shaken by the whole business. It leaves him unsettled. And as both you and Lucy (below) said, the laboriousness of the film is really on point with the original text. Perhaps that “holy grail” of HOUN films will be able to combine the reality of the HOUN text, with how devotees of that particular story seem to perceive it! Thank you again!

ReplyDelete@Lucy: Thank you so much! I think everyone involved in the Granada series was perfectly aware of the parameters of the original text. In fact, I was a bit surprised to read in Davies book that Brett thought the script wandered and that Holmes was away too long. Of course—that’s how Doyle wrote the story! But as I said to Live Out Loud, I think the issue with HOUN adaptations is finding a balance between the confines of the original text and how fans actually perceive the story. It’s a balancing act. And regarding “Alastair Duncan” (I did a double-take too), if you look at his filmography, you’ll see that he often performed under different names. He actually did HOUN under the name “Neil Duncan”!

@KateM: I think your observations are spot-on. Granada was wonderfully meticulous in most of the episodes and adaptations, but sometimes directors and producers need to step back and realize what just *won’t* work on screen. There are limitations, not everything is going to make it. I would have loved to see Brett get his second shot. It was poignant to hear that was something he really wanted. Personally, I would have loved to have seen Granada’s version of STUD—to see how they would have come to terms with their older stars and their younger counterparts. Thank you for your comment!

@virtualight: Mea culpa! I am so sorry! :-) Perhaps you will one day forgive me? ;-)