“Upper Swandam Lane is a vile alley lurking behind the high wharves which line the north side of the river to the east of London Bridge. Between a slop-shop and a gin-shop, approached by a steep flight of steps leading down to a black gap like the mouth of a cave, I found the den of which I was in search” (TWIS).

The beginning of “The Man with the Twisted Lip” finds Dr. Watson comfortably ensconced in his cozy armchair, in his cheerful sitting-room, with his wife contentedly doing needlework by his side. It is the very picture of domesticity and marital harmony, and it appears that Watson has finally acquired that “tranquil English home” that he seemed to desire so very much in The Sign of Four. But his pleasant and peaceful existence is soon abruptly disturbed, and for once, it is not even Sherlock Holmes’s fault. Dr. Watson soon finds himself at the Bar of Gold, an opium den, on Upper Swandam Lane, in search of Isa Whitney, the husband of one of Mrs. Watson’s old school friends. While there, the Doctor finds both Isa Whitney and Sherlock Holmes, and is plunged into an entirely new mystery.

The Bar of Gold is a vile establishment, in an even viler neighborhood, but it serves its purpose as a setting, in that it creates very clear and clean contrast amongst the story’s various locales. According to Rosemary Jann, author of “In the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: Detecting the Social Order,” the “…pervasive pattern of Holmes and Watson departing from the snug comforts of their Baker Street rooms to invade the dark and stormy world outside symbolizes the vulnerability of middle-class domesticity that so often lies submerged in these plots.” Surely no place can be as “dark and stormy” as that which Dr. Watson describes:

“Through the gloom one could dimly catch a glimpse of bodies lying in strange fantastic poses, bowed shoulders, bent knees, heads thrown back, and chins pointing upward, with here and there a dark, lack-lustre eye turned upon the newcomer. Out of the black shadows there glimmered little red circles of light, now bright, now faint, as the burning poison waxed or waned in the bowls of the metal pipes. The most lay silent, but some muttered to themselves, and others talked together in a strange, low, monotonous voice, their conversation coming in gushes, and then suddenly tailing off into silence, each mumbling out his own thoughts and paying little heed to the words of his neighbour.”

In The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Leslie Klinger notes that there is actually no “Upper Swandam Lane,” and that a variety of Sherlockian scholars have been unable to decide upon a substitute location (162). Furthermore, the “Bar of Gold” was likely a disguised name for various similar locations throughout London and remarks that several notable writers included comparable opium dens in their works: “J. Hall Richardson’s ‘Ratcliff Highway and the Opium Dens of To-Day,’ which appeared in Cassell’s Saturday Journal of January 17, 1891, described a ‘Mahogany Bar’ among other dockside haunts of ‘wilt Lascars.’ In Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone (1868), the opium den was named The Wheel of Fortune” (161).

Whether or not the opium den of TWIS is an actual site or no, if something dreadful and immoral were to take place—if someone were to do something dreadful and immoral—then the Bar of Gold is certainly the place for it to occur. And if something astonishing, or revelatory bordering on miraculous were to transpire—then what better place than a cheerful English sitting-room, or country villa, or even a well-lit prison cell at Bow Street (with some water, soap, and a large bath sponge, for goodness sake)?

After encountering the Detective at the Bar of Gold, Watson puts Isa Whitney in a cab and sets off with Holmes for The Cedars, which is the St. Clair family villa, near Lee, in Kent. Dr. Watson has already had two surprises this evening—the startling appearance of Kate Whitney at his doorstep and finding Sherlock Holmes crouched in the corner of the Bar of Gold—and he will be subjected to several more before the case is concluded. As they drive, Sherlock Holmes provides Watson with the details of Neville St. Clair’s disappearance—how the man was last seen in the upper window of the Bar of Gold, and that it appears the respectable gentleman was brutally murdered by a filthy beggar named Hugh Boone, who claims residence at the ghastly opium den.

The scene at The Cedars—“a large villa which stood within its own grounds”—by contrast is remarkably charming and hospitable. Mrs. St. Clair shows them into “…a well-lit dining-room, upon the table of which a cold supper had been laid out…,” and it is in this convivial atmosphere that Mrs. St. Clair makes the next astonishing revelation of the evening: she has received, just that day, a letter from her missing husband, and man that Sherlock Holmes has just told her was likely dead. After retiring to the double-bedded room provided by Mrs. St. Clair, Watson’s paints one of the more lasting pictures of Sherlock Holmes:

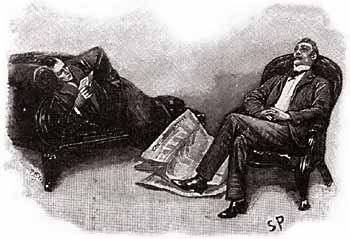

“He took off his coat and waistcoat, put on a large blue dressing-gown, and then wandered about the room collecting pillows from his bed and cushions from the sofa and armchairs. With these he constructed a sort of Eastern divan, upon which he perched himself cross-legged, with an ounce of shag tobacco and a box of matches laid out in front of him. In the dim light of the lamp I saw him sitting there, an old briar pipe between his lips, his eyes fixed vacantly upon the corner of the ceiling, the blue smoke curling up from him, silent, motionless, with the light shining upon his strong-set aquiline features.”

Holmes seems quite comfortable, even satisfied, if not exactly relaxed in his surroundings. Eventually Watson drops off to sleep and is awoken by Holmes’s cry of sudden realization: “[Sherlock Holmes] chuckled to himself as he spoke, his eyes twinkled, and he seemed a different man to the sombre thinker of the previous night.” After a night of quiet reflection on his homemade settee, Holmes now has the key to the whole mystery, which he has stolen from the St. Clair’s bathroom, in his Gladstone bag.

Upon arriving at Bow Street, Holmes and Watson are taken to Hugh Boone’s cell by Inspector Bradstreet. There is no direct description of Boone’s cell—and logically it is probably not an extremely cheerful place—but it seems to be well-lit since Bradstreet says: “You can see him very well.” The situation seems to lighten further when Holmes reveals the cleaning implements he has brought with him. It is well-known what happens next: the Detective takes the soap and sponge to Hugh Boone’s face and scrubs away the beggar’s façade to reveal the face of Neville St. Clair underneath. It is the last great, astonishing revelation of the case. As Bradstreet says, “Well, I have been twenty-seven years in the force, but this really takes the cake.”

On the surface, the differences between the Bar of Gold in Upper Swandam Lane, and the other more hospitable locations in TWIS, are really so obvious as to seemingly defy any lengthy discussion. However, it is what happens at each of these locations and the frequency with which they occur that is really the crux of the matter. Indeed, rather than seeming to be foul for the sake of being foul, it is the very nature of the Bar of Gold that promotes that behavior at the other settings: Dr. Watson’s residence, The Cedars, and the Bow Street cells. It highlights the more astonishing revelations; illuminating and making them appear nearly miraculous in detail: Kate Whitney’s arrival, Sherlock Holmes appearing in the opium den, Mrs. St. Clair’s receipt of a dead man’s letter, and the face of that dead man appearing beneath the face of a vagrant. And for its part, the Bar of Gold is a reminder of just how dark things can appear, and how desperately a little light and wonder is sometimes needed.

oOo

Sources:

Jann, Rosemary. “In the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: Detecting the Social Order.” New York: Twayne Publishers, 1995.

Klinger, Leslie. The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes (Volume 1). W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

I have often recoiled at the visits of these dear characters to the Bar of Gold. Hence, I was very interested to read your analysis of how it is used not only as an unavoidable plot element in certain mysteries, but thematically as a contrast to the shelter of Baker Street. Furthermore, the pull that Holmes feels to this other side of life says a lot about his character, and not only in reference to his addiction. His "dressing up" in disguise fills a deep need in him, as does a sort of identification and vicarious living through his clients and even more so, the perpetrators of the crimes he investigates. It is a rare combination of curiosity, compassion, zeal for truth and justice, and pride in his own remarkable skill. The fact that he remains only a visitor in Swandam Lane, rather than a denizen of its darker abodes, testifies to his strength of character, perhaps even a victory in a struggle with himself, don't you think?

ReplyDeleteI love your ending because Holmes is so thoroughly a bringer of "light and wonder" to such dark places, a Diogenes himself indeed.