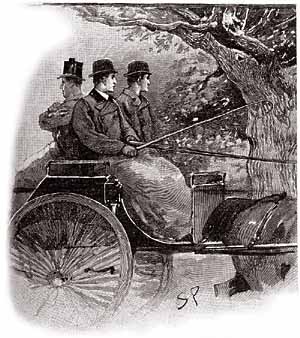

In the 1986 Granada Television adaptation of “The Musgrave Ritual,” Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson arrive at Hurlstone Manor for a holiday

– much needed (on Holmes’s part) and much encouraged (on Watson’s part). They

are greeted by Reginald Musgrave, and the conservation is polite, if a little

stilted. Finally, Holmes and Musgrave walk off alone – leaving Watson in

friendly conversation with Brunton, the butler. Musgrave compliments Holmes on

making a successful living off of his wits, to which Holmes replies, while

looking about absently: “And how is the dear wife?” A brief silence follows

before Musgrave replies: “I’m not married, Holmes.” There is another, longer,

more awkward silence before Holmes claps Musgrave on the shoulder: “How wise!”

|

| Photo Credit: bookishadventures.tumblr.com |

And that is the disconnect with Reginald Musgrave; that is

what separates Musgrave from other figures from Sherlock Holmes’s past – Victor Trevor, for example. Although the plot of MUSG was slightly altered for the

Granada adaptation to compensate for the somewhat advancing ages of the series’

stars – Jeremy Brett, for example, was 53-years-old at the time of filming and

was therefore perhaps ill-suited to play the 25-year-old Sherlock Holmes as seen

in the original text of MUSG – the dynamic between Holmes and Reginald Musgrave

remains true to the source material. Holmes and Musgrave are not friends. That

is not to say that they are antagonistic, far from it. They are merely

acquainted. Musgrave spins in and out of Sherlock Holmes’s orbit in much the

same way as any of his other clients. At times there seems to be no difference

between Reginald Musgrave and Violet Hunter, Victor Hatherley, or Grant Munro –

that is to say, once they have served their purpose, they are rarely, if ever,

heard from again. Musgrave at least has the added benefit of being openly

appreciative of Holmes’s talents, where many had seemed initially incredulous: “Once

or twice we drifted into talk, and I can remember that more than once he

expressed a keen interest in my methods of observation and inference.”

But like Victor Trevor, Reginald Musgrave intrigues because

he knew Sherlock Holmes when. He knew

him when he was young and was not yet

fully formed or fully in possession of his powers. He knew him when his career as the world’s only

consulting detective was not yet sculpted out or defined to his satisfaction.

More importantly, Reginald Musgrave knew Sherlock Holmes when Dr. Watson did not. Reginald Musgrave was present at the beginning of Sherlock Holmes – which for

some Sherlockians is somewhat equivalent to being present for the Big Bang –

and so he is in possession of a piece of the puzzle, which we are not. But does

that truly lend any extra weight to Musgrave’s presence in the Canon – does

that give him more merit as a character, when Holmes appears to give him the

same level of consideration as the dottles and plugs of tobacco left on the

mantelpiece of Baker Street every morning?

Unlike Victor Trevor, who was present from the very

inception of Holmes’s career (“And that recommendation, with the exaggerated

estimate of my ability with which he prefaced it, was, if you will believe me,

Watson, the very first thing which ever made me feel that a profession might be

made out of what had up to that time been the merest hobby.” [GLOR]), Holmes

appears to lose track of Reginald Musgrave for a bit of time before their paths

cross again: “For four years I had seen nothing of him until one morning he

walked into my room in Montague Street. He had changed little, was dressed like

a young man of fashion–he was always a bit of a dandy–and preserved the same

quiet, suave manner which had formerly distinguished him.” Holmes’s description

of this first meeting with a long-lost acquaintance is rather interesting, in

that he manages to both insult and compliment Musgrave in the same sentence. It

is up to the reader to determine if the balance of the remark is ultimately

neutral. But the casual way in which Holmes marks the length of their separation

indicates that it was all the same to him if Musgrave had never walked through

his door at Montague Street at all, save for the puzzle he brought with him.

According to Leslie Klinger: “Holmes and Musgrave were never

more than ‘slight acquaintance(s)’: thus it is possible that the struggling

young detective saw not a social visit but a business opportunity when Musgrave

walked through his door. June Thomson speculates that Holmes may have charged Musgrave

a fee for his services, pointing to his ‘living by my wits’ remark as ‘possibly

a hint that he had turned professional and expected to be paid’” (534). And so,

the reader sees Reginald Musgrave present at the time when Holmes has begun to

realize that his services had value.

Musgrave may not be the Detective’s first paying client, but he was probably

one of the earliest. Victor Trevor may have been present for the beginning of

Sherlock Holmes, but Reginald Musgrave was present for the event horizon – for the

point of no return, for the moment when Holmes’s fate was fully determined and

guaranteed.

As has been mentioned before, Holmes ultimately lost track

of Victor Trevor – just as he lost track of Musgrave – but that was hardly

Holmes’s fault entirely – the sordid circumstances surrounding his father’s

death were certainly enough to make a reasonable man want to escape any and all

places and persons associated with the events. The weight and merit of Trevor’s

character rest largely on what he was present for, and Musgrave bears much the same burden. Though of the two

men, Victor is the only one who can honestly wear the title of “friend,” Musgrave

is the only one who can be honestly called a “client” – in the fully paying

sense of the term. And while Victor Trevor sought out Sherlock Holmes in his hour of need, Reginald Musgrave walked

through the door of Montague Street looking for a detective.

oOo

“Better Holmes & Gardens” now has its own

Facebook page. Join by “Liking” the page

here, and receive all the latest updates, news, and Sherlockian tidbits.

Your thoughts on Reginald Musgrave suggest a further blog post on similar aristocrat portraits - Sir Henry Baskerville, Musgrave,the Duke of Holderness seem bound and shaped by their ancestry... whereas Holmes(and Watson) are free Bohemian souls. Perhsps Holmes senses he and Musgrave inhsbit different planets.

ReplyDeleteYour approach in this essay is so illuminating because, as individually distinctive a person as Sherlock Holmes is, he is also a man enmeshed in a web of important relationships to friends, associates, clients, adversaries and, of course, his inimitable brother. However antisocial Sherlock's temperament appears at times, he is inescapably a social being, as we all are. One element of Conan Doyle's genius is the way he situates his thoroughly eccentric character in an equally eccentric network of associations. I love the way you bring out the rich significance of his rather slight connection to Reginald Musgrave. Holmes couldn't become Holmes, the private consulting detective, on his own; he needed that first client. Musgrave did him a better turn of friendship than any personal sympathy between them could have achieved, as you show.

ReplyDeleteI admire Granada's brave attempt to adapt The Musgrave Ritual, though I don't think it was quite successful. And it lost this added element of youth--what really happened around the time that Holmes burst on the scene, seemingly sui generis. :)