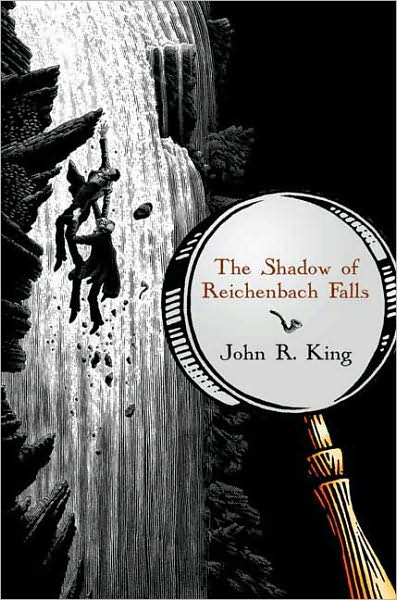

John R. King; Publisher: Forge Books (August 5, 2008)

I pulled my left hand away and began walking, a tingle of dread moving up my spine. “I know who I am. Who are you, Silence? Read your own palm.”

Silence matched me stride for stride. “I have been. Of course I have. There are many scars there for so thin a hand. The palm has tobacco burns, the sort that would come from embers falling from a pipe, and acid burns from mixing caustic chemicals. The back of the hand has black powder scars from firing a gun, and here—do you see these?” He rolled back his sleeve and showed me the purple depression of veins leading from his inner elbow.

“Opium.”

“More likely, cocaine. These are recent scars” (75-6).

Like most people, I think, I tend to judge a book based upon two criteria: the impression the book leaves on me initially, and the impression it makes on me over the long term. More often than not, these two impressions are the same, but it’s when they differ that things get really interesting. Such was the case with John R. King’s (more popularly known to fantasy-enthusiasts as J. Robert King) The Shadow of Reichenbach Falls—I put the book down thinking, amongst other things, “What a very...strange story,” but found that details of the book were hard to shake off over time. I found myself coming back to it, rereading passages, until the book spent more time off my shelf, than on.

Set against the events of “The Final Problem,” the novel offers an alternative plotline to the proceedings that took place leading up to, and during, the Great Hiatus. During 1891, the young Thomas Carnacki [Note: If you are unfamiliar with author William Hope Hodgson’s Victorian ghost-finder Thomas Carnacki, you can find an excellent primer on him here.] is in the midst of a lovely picnic with a beautiful, though strange, young lady named Anna, whom he meets in Switzerland. As they sit at the base of the Falls, the couple witnesses a fight on a cliff above them, and watches, horrified, as one man tosses the other into the river below.

|

| Thomas Carnacki |

While the amnesiac man is obviously Sherlock Holmes, and the man who tossed him over the Falls is obviously Professor Moriarty, that is where everything that is “obvious” about the story ends. The reader can ask any number of questions at this juncture—What will Thomas do? What is lovely Anna's story? How on Earth did the elderly, feeble Professor Moriarty throw the much younger, stronger Sherlock Holmes over the cliff? And, what is Sherlock Holmes without his great mind? Is he even Sherlock Holmes at all?

King’s amnesiac-Holmes is in many ways very much like himself, as the passage above indicates. But he is also in some ways very childlike, unable to ascertain how he accomplishes certain things. At times he seems equally confused and terrified by his abilities, and at others, amused by them. He seems disproportionately trusting, more dependent on others, and more aware of his physical needs than he would be with his memory intact (in fact, when Silence/Holmes expresses hunger or a desire for sleep, it is almost shocking, in a way; as if he had expressed a preference for frilly hair ribbons or to join a corps of dancing girls). Not knowing any better, however, Thomas and Anna take everything in stride as they set about getting Silence’s mind back.

And Sherlock Holmes’s mind is ultimately what is at stake here. It is what the entire plot hinges on and revolves around—not just Holmes’s memory, but his mind. As Moriarty says:

“Yes. That is the problem. This brain of yours. Empty. It’s not what I paid for. It’s the attic without the treasure… It’s as if the library of Alexandria had burned! […] It did burn, my friend. That library, with all the wisdom of the ancient world—that goddamned library is gone. Gone! And your goddamned mind is gone, too. All that you knew, all that you were—gone, except this pathetic, festering hunk of meat… (117)."

If Moriarty seems a tad more vicious than you’ve come to expect, I assure you there is a very interesting, if implausible reason for it; and the book is worth reading, even if all you want to do is discover what the reason is. More interesting for myself, however, was who Sherlock Holmes became (“Harold Silence”) when he was no longer aware of himself. As Holmes’s mind comes back to him, in bits and pieces over the course of the story, it is as if the framework of his character is reassembling itself, and the reader can suddenly see the foundation of Sherlock Holmes. It’s almost as if the most important characteristics that made him uniquely Sherlock Holmes are what fall into place first—his deductive abilities, his imperious nature, and, of course, even his friendship with Dr. Watson:

“And there is a listener beside me. He is a stocky man with an intelligent face and sensitive eyes…I look upon this slumping figure, who takes in my violin playing as a drunkard takes in gin, and I see greatness in him. Greatness and friendship (90).”

This is all King’s interpretation, of course, but The Shadow of Reichenbach Falls is an excellent read for anyone who has ever chased the answer to the ever elusive question of Holmes’s essential nature, the structure that supports the Great Detective. Stripped of nearly everything that distinctly characterizes him, Harold Silence/Sherlock Holmes makes for an interesting personality study, but barring that and underneath it all, John R. King proves that Sherlock Holmes is still a great man. Even if he has to be reminded of it.

Your review has inspired me to pick up the book. Do you think it would be something a non-avid Sherlock reader would enjoy? Are there any prerequisite books you would suggest?

ReplyDelete" I found myself coming back to it, rereading passages, until the book spent more time off my shelf, than on." I love books like that, the ones that catch us by surprise.

@Lynette: Definitely let me know what you think when you finish! I think it's a good cross-genre book for reasons that I couldn't get into in the review without revealing huge chunks of the plot. And I wouldn't say there are any pre-requisites but you may enjoy reading "The Final Problem" and "The Empty House" after you finish (to give you context for the original plot).

ReplyDeleteYou can find them both here: http://ignisart.com/camdenhouse/canon/index.html

Lynnette fastened on the same sentence I did! "...the book spent more time off my shelf, than on." This review may put the book ON my shelf, for a while at least!

ReplyDeleteI also like the theme that it tries to get at Holmes' "real" nature, in the era where scientific psychology and spiritualism were both vying for the hearts and minds of intellects as deep as Conan Doyle's.

Thanks for an intriguing review, and I like learning enough to get me excited over it.

~Lucy Pollard-Gott

@Lucy: If you get to read it, please let me know what you think. I've found that I'm in the minority in liking this book, since I look at it as a character study of Sherlock Holmes. But there's a rather large subplot that some people find off-putting (and I'll admit that I found rather silly when I first read it). There is also a very deep vein of psychology and spirtualism in the novel, which I think is what so intrigued me.

ReplyDelete