Sherlock: “…I mean, what is there for me to do?”

Mycroft: “To act, Sherlock. To act. All my instincts are against this explanation, and your’s too, I think. We are not brothers for nothing. Use your powers, go to the scene, question the people concerned, leave no stone unturned. In all your career, you’ll never have a greater chance of serving your country.”

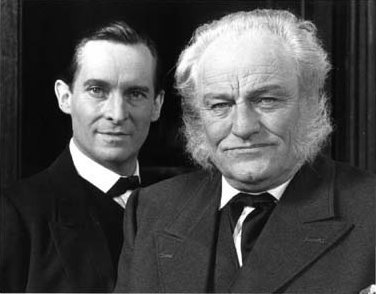

(“The Bruce-Partington Plans,” 1988)

(“The Bruce-Partington Plans,” 1988)

Quite a bit of Sherlockian scholarship is devoted to the question of whether or not Sherlock Holmes could have existed in a vacuum. Could he have deduced as easily from Montague Street as from Baker Street? Would he have been able to solve crime as a chemist working in the laboratories of St. Bart’s? And, perhaps most pressing, does Sherlock Holmes even exist without Dr. Watson by his side?

For my part, I’ve always been more than a little bit fascinated by the relationship between Sherlock Holmes and his older brother, Mycroft. My perception of their relationship has been colored by some of the remarkable on-screen portrayals over the years. Not the least of which is that of Charles Gray’s Mycroft to Jeremy Brett’s Sherlock; but more recently we’ve seen Mark Gatiss as older brother to Benedict Cumberbatch; and much buzz is already brewing about Stephen Fry’s portrayal of the older Holmes sibling, opposite Robert Downey, Jr., in Guy Ritchie’s sequel to his 2009 blockbuster, which is due out later this year.

Mycroft Holmes, for all that he is apparently Sherlock’s only living relative, appears in just two of the original stories: “The Greek Interpreter,” and “The Bruce-Partington Plans.” He is also briefly mentioned in “The Final Problem,” and “The Empty House.” He is one of the founding members of the Diogenes Club (a club for misanthropic men), superior to his brother in both intelligence and deductive skill, and, as Dr. Watson puts it, rather…rotund:

“Heavily built and massive, there was a suggestion of uncouth physical inertia in the figure, but above this unwieldy frame there was perched a head so masterful in its brow, so alert in its steel-gray, deep-set eyes, so firm in its lips, and so subtle in its play of expression, that after the first glance one forgot the gross body and remembered only the dominant mind (BRUC).”

Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson are flatmates for more than seven years before Sherlock reveals his brother’s existence and introduces him to Dr. Watson in “The Greek Interpreter.” And frankly, you have to wonder why Mycroft needed to enter the picture at all. Everyone seemed to be getting on just fine without him. Sherlock was deducing, making daring leaps of intellect, and even battling poisonous snakes, while the world thought, as Watson did, that “…he was an orphan with no relatives living” (GREE).

There was seemingly nothing wrong with thinking that the world only had space for one terrifyingly intelligent man, who could know the shape of you by the pattern of your footfalls. What are the readers supposed to do with two men of startling genius, even if one of them is (gently put) less inclined to physical efforts? Why wasn’t one Holmes enough?

Therefore, I think you have to consider the Holmes brothers as a set in order to go about answering that question. In her 2010 novel, The God of the Hive, Laurie R. King makes an interesting observation:

“The Holmes brothers were a bit god-like: generous and well meaning towards lesser mankind, but capricious and sometimes frightening in their omniscience (47).”

The reader should consider Sherlock and Mycroft as an entity, consider them as a pair, consider what is accomplished when the two of them work together (or do not, as the case may be). Sherlock is the unstoppable force to Mycroft’s immovable object. Sherlock makes mistakes, and he also been outwitted. But Mycroft often needs help because of his own physical limitations. Together, they are a veritable fortress of intellect. Who wouldn’t be a little frightened? They are unemotional, unmovable… and really very uninteresting.

And so it’s easy to see why Mycroft wasn’t around at the beginning, why Sherlock didn’t make a point of introducing his new flatmate to his only family in A Study in Scarlet, and why Mycroft only made sporadic appearances throughout the canon. Because when the Holmes brothers are together—the conclusion is nearly forgone. How can the mystery not be solved? It would get a bit boring after awhile, I think.

But when they are together, the reader can’t help but remember that we are “lesser mankind,” as King puts it. When Sherlock is solving crime with Dr. Watson as his partner, the reader can look to the good doctor as a reminder of all that is normal, and attainable, and accessible, and the Great Detective suddenly doesn’t seem so out of reach. We feel as if it might even be possible to imagine ourselves in the doctor’s position, using our own normal brains to assist, as Watson does on occasion.

But paired up with, and standing alongside his equally astonishing brother, the reader can’t help but be reminded of why Sherlock Holmes is so truly extraordinary, and beyond our ability to fully comprehend. Mycroft accentuates and reinforces all that so otherworldly about his brother, and throws it all into stark relief. We can’t help but see it all, because we are seeing it in double.

We remember that Sherlock is unique, that he is exceptional, and he is, most certainly, not like the rest of us. Mycroft Holmes serves as a reminder of the company that Sherlock should be keeping, of what he could potentially achieve, if he weren’t so caught up in our lesser problems. The reader feels more grateful, after seeing Sherlock with Mycroft. They are, indeed, “a bit god-like,” when they are together, and the reader feels grateful that Sherlock Holmes would choose lesser mankind at all.

They are not brothers for nothing, it would seem, after all.

Wonderful quote from Laurie R. King, and I like where you took it in your conclusion: Sherlock's humanity is revealed in his conscious choice of "lesser mankind" as a field of action. He does not choose to be a denizen of a rarefied Laputa of the mind. Instead, he tests his science of detection in the world of Everyman's "peculiar problems." A genius who can never fail has not tried for all he could be!

ReplyDeleteI love your affectionate analysis of the Holmes brothers and how they complement and challenge each other. Their relationship also complements the voluntary brotherhood of Holmes and Watson--which, I have no doubt, you will explore further in a future post! :)

This is a great analysis of these two. I've always thought it a fascinating dynamic as well, and you know, I agree that it's an interesting choice to introduce Mycroft so late in the game. They play off each other very well. I wonder also if Conan Doyle wasn't also trying to humanize Sherlock even further by introducing a character who could match him intellectually, and even one-up him occasionally.

ReplyDelete