“There are many men in London, you know, who, some from shyness, some from misanthropy, have no wish for the company of their fellows. Yet they are not averse to comfortable chairs and the latest periodicals. It is for the convenience of these that the Diogenes Club was started, and it now contains the most unsociable and unclubable men in town. No member is permitted to take the least notice of any other one. Save in the Stranger’s Room, no talking is, under any circumstances, allowed, and three offences, if brought to the notice of the committee, render the talker liable to expulsion” (“The Greek Interpreter”).

Of all the characters in the Sherlock Holmes canon, I’m probably the most partial to Mycroft Holmes. I think it has something to do with being an older sibling myself; often corralling a younger sister who seems to loathe all civilized society with her “whole bohemian soul,” and occasionally seems intent upon upsetting our mother whenever possible. Whatever the reason, I find myself drawn to the stories prominently featuring Sherlock Holmes’s older brother, and to the bizarre gentlemen’s club with which he is so inexorably connected. The club’s strangeness, in both rule and atmosphere, only serves to augment Mycroft Holmes’s own personal eccentricities, and therefore the oddities of his famous brother (if only by association), by keeping all elements contained within a hermetic atmosphere.

It’s difficult, if not impossible, to separate Mycroft Holmes from the Diogenes Club, which he co-founded. It is a club for men who enjoy peace and quiet, and who eschew social interactions. It is a society for men who find the company of other men superfluous, and would rather live their lives without distraction and with little human contact. Members can even be expelled from the club for speaking, which sounds quite marvelous to those of us eternally in search of silence, never seeming to find it. Even the local library always seems to have one occupant who believes that his earphones are enough to block out the noise of his iPod, when they most certainly are not.

But according to Leslie Klinger’s The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, the Diogenes Club and its litany of peculiar demands was not, in reality, all that strange, given time and place:

“As bizarre as the Diogenes’s practices might seem, such an attitude was de rigueur at most London clubs, where bachelors and married men alike could both relax and cultivate an air of exclusivity and high social rank…That the Diogenes had a designated Stranger’s Room seems similar to the Athenaeum’s policy of relegating its members’ friends to a small room near the club entrance” (641-2).

So, if the Diogenes Club is not that far removed from the norm as far as Victorian gentlemen’s clubs are concerned, than what is it about the place that is so compelling? The Diogenes Club is only mentioned directly in two Sherlock Holmes stories—“The Greek Interpreter” and “The Bruce-Partington Plans”—but as with so many Sherlockian things (like Irene Adler, the iconic Deerstalker and pipe, and the Giant Rat from last week’s post), it has taken on a life on its own, beyond the confines of the text. The answers seem to lie within, not only the boundaries of the club itself, but within what the Holmes brothers make of it.

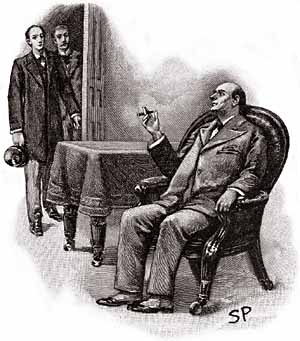

In “The Greek Interpreter,” Mycroft convinces his brother to sit with him in the bow-window of the Stranger’s Room, within moments of Sherlock and Dr. Watson’s arrival at the club. “To anyone who wishes to study mankind this is the spot,” [says] Mycroft. “Look at the magnificent types! Look at these two men who are coming towards us, for example.” What follows is a brilliant example of Holmesian deduction, as Sherlock and Mycroft bat back and forth a series of logical inferences, regarding a non-commissioned officer who had just happened to wander into their viewing.

|

| bookishadventures.tumblr.com |

But even when Mycroft Holmes is on his own, the Diogenes Club still works to create a sense of separateness and otherness. In “The Bruce-Partington Plans,” Sherlock marvels at the telegram announcing his brother’s imminent arrival at 221B Baker Street. He explains to Watson: “It is as if you met a tram-car coming down a country lane. Mycroft has his rails and he runs on them. His Pall Mall lodgings, the Diogenes Club, Whitehall—that is his cycle. Once, and only once, he has been here. What upheaval can possibly have derailed him?” And he says later, “A planet might as well leave its orbit.”

In short, Mycroft Holmes does not go places, as other people do. He does not run errands, or take walks in the park, or even jump into a hansom cab to visit his only (for the purposes of the canon, Mr. Baring-Gould) brother. He is not like Sherlock; he is not known anywhere and everywhere. Therefore, the places that Mycroft chooses to honor with his presence are significant. When a man divides his time equally amongst work, lodgings, and club—and nowhere else if he can manage it—the mere act of having a club at all says a great deal about the space. Mycroft gives the Diogenes Club a sense of exclusivity merely by occupying it. And if Mycroft also chooses to keep himself separate from the rest of humanity, then the Diogenes Club is the place to do so—a place where no one will question Mycroft Holmes, his actions, or his work because they are not allowed, or even maybe because they simply do not care. At the Diogenes Club, he is free to be Mycroft Holmes, with all the weight of what that statement implies, more than in any other location in London.

I’ve spoken elsewhere on the relationship between Mycroft Holmes and his younger brother, about their inherent god-like qualities and how Mycroft serves to highlight Sherlock’s service to the rest of us lesser mortals, how Mycroft makes the reader grateful that Sherlock chose our human problems and everything that might entail. The Diogenes Club merely serves to highlight Mycroft in a similar fashion, emphasizing his own particular abilities and attitudes. The idea of the Diogenes Club will probably always appeal to the socially awkward and misanthropic among us, those who would rather observe the world behind a glass partition than interact with it. And also to those who are just looking for five minutes of quiet to finish a blog post, away from the sounds of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare II. But I wouldn’t know anything about that.

oOo

Now you can join the Diogenes Club! Join a body of fans from across the globe in providing live commentary on the immense catalog of Sherlock Holmes films and television series. The club is available online and on Twitter. Join the discussion on Twitter using the hashtag: #221B.

And just a reminder that a new blog contest will begin on June 27, so check back here for more details!

Top quality post as always.

ReplyDeleteAgreed, another excellent post and it does make me wish the Diogenes Club existed. If only the Junior Ganymede and Drones clubs could also exist somewhere. The world would probably be a nicer place. And just think what Holmes could do with the Junior Ganymede club book.

ReplyDeleteGreat post (and I, too, wish there were a Diogenes Club to join). There's certainly a difference between the aloofness of Mycroft and the unsociable personality of Holmes. Mycroft really is the one who wouldn't have any close friends, whereas Holmes, for all his eccentricities, at least likes to lecture on his work, to Watson.

ReplyDeleteThis is a wonderful post. Thank you. I have always thought most highly of Mycroft and I didn't quite believe Watson's reports. Thus I sought an alternate explanation, because I have always thought something more was going on in the Diogenes club than met Watson's eye.

ReplyDeleteFor instance, if you were to wander around inside NSA without a Top Secret clearance people would act strangely even if you had legitimate business there.

@Alistair: Thank you very much! That means a great deal coming from you! :-)

ReplyDelete@Virtualight: I could not agree more. There's a very long list of fictional places that would make the world a little nicer if they were real. And you also got me thinking...with nearly 10,000 Sherlock Holmes pastiches out there (and the list growing everyday), someone must have taken on "Holmes meets Jeeves," and I need to find it! Thank you!

@Marian: You are quite right. There is a distinct difference between Mycroft’s and Sherlock’s attitudes on social interaction. Sherlock seems to have no use for people until he needs an audience (but he *will* always need one, eventually). And Mycroft seems to have very little use for humanity, ever, under any circumstance. I’m reminded of the end of Granada’s version of GREE, when Mycroft tells Sherlock that the only path he intends to take is “…the door to the Diogenes Club, which I shall close behind me!” Thanks for commenting!

@Steve: Thank you for your very kind comment! What a great analogy—very thought-provoking! I’m sure you’re familiar with Kim Newman’s books about the Diogenes Club? And I’ve always liked Alan Moore’s take on Mycroft and the Diogenes, in “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” graphic novels. I think it’s only logical to wonder if a silent façade as something brewing under the surface!

This Post is awesome. Well thought out and it makes me yearn for that quiet space. To be with people yet sort of protected from having to actually interact!

ReplyDeleteAnd I do love the relationship between the brothers and how different pastiches, tv shows and movies have expressed it.

@Live Out Loud: Thank you very much! Doyle used Mycroft Holmes so sparingly in the stories that it left a lot of room for interpretation. On the one hand, he has a specific routine from which he's reluctant to deviate (BRUC), but on the other hand, he's willing to disguise himself and drive a cab when his brother's life his on the line, as we see in FINA. That's a lot of middle ground for writers to work with!

ReplyDeleteI especially like the point implied in your discussion that Mycroft shows us what Sherlock might have been if his bent toward misanthropy did not admit of activity and social interaction. Ironically, it adds a dimension of warmth to Sherlock's character, since he takes such a determined interest in people and an active part in resolving their "little problems."

ReplyDeleteConcerning the yearning to visit the fictional club, mentioned by @Virtualight, and seconded by you, I agree that one could easily compile a list, a "Fictional Places 100" perhaps, full of satisfying or intriguing spots for a virtual vacation! Holodeck, start program, please!

@Lucy: There are several key differences between Sherlock and his older brother, and I think how each brother approaches social interaction is a crucial one. Sherlock may have an abbreviated use for humanity and their limited powers, but he does have a use for them. He may not need an audience all the time, but he does need one. I don't think it's too much of a stretch to imagine Mycroft living separate from society for the rest of his days, and being perfectly content in his isolation. On the other hand, even when Sherlock is in retirement, he can't quite stay away from people.

ReplyDeleteAnd what a great book "Fictional Places 100" would make! And what fun to preface it under traveling in a computer simulation, or "holodeck." I'd be first in line for a copy. :) Thank you for commenting, as always, Lucy!